100 Rejections

For a talk to graduating art school students, and also anyone else applying for jobs.

This talk is about how I got my first job after art school. But really it is a talk about creativity.

D.W. Winnicott, the psychoanalyst, described “creativity as a feature of life and total living.” He opposed this creativity to artistic achievement.

He said, “a successful artist may be universally acclaimed and yet have failed to find the self that he or she is looking for. The self is not really to be found in what is made out of products of body or mind…If the artist…is searching for the self, then it can be said that in all probability there is already some failure for that artist in the field of general creative living. The finished creation never heals the underlying lack of sense of self.”

Riffing on Winnicott’s idea of “general creative living”, I propose that the most pressing question ahead of you is not the future of your art careers, but how you will invent and reinvent mundane forms, even ones as banal as a job rejection.

In my final year of art school, while I pressed and prodded and produced, I moved around in a state of unspoken worry, unsure how I would financially survive after graduation.

During those months, I listened to podcasts, filling time with the chatter of other people’s streamed words.

It was a weird moment, and little of what I heard stuck in my head. But a few things did, and one of them was a podcast about Jia Jiang, a man who was terrified of rejection.

I was in the print room, my hands sweating in latex gloves, when I heard his voice thread with the presenter’s as they described how Jiang decided that he would systematically encounter rejection again and again – specifically, until he got 100 rejections.

His idea had come from one of those psychological kooks who come up with new and bold therapies with strange and unappealing names. ‘Rejection therapy’ was meant to work like any other exposure-based treatment, where instead of avoiding the fear, the person would approach the terror until it no longer terrified them.

The episode told the story of his rejection quest, which included making hundreds of bizarre appeals. For example, he asked for $100 from a security guard and went to his dog groomer and requested her to cut his hair. She laughed, and then said no.

The gift of art school is that you are given licence to take your own ideas and other people’s seriously. You are encouraged to experiment in new forms, new ideas, new ways to live.

For reasons of vulnerability and fear, Jiang’s quest seemed to me like one of those new ideas.

I knew I had to get a job. I had no idea what to do. So why not put all that angst and energy in getting rejected 100 times?

Looking back on it now, I think the reason why I was so willing to take on this quest was because it was formally inventive.

To me, he had destroyed and re-formulated the meaning of rejection’s essential form.

Let me explain the logic. Rejection – like any other social interaction – has a customary shape, and to understand its form makes clear why its more painful aspects can be re-engineered.

All rejections are social rejections, because they happen in the context of a social world, so the meaning of rejection should be determinative.

When we ask, would you? Can I? Let me? And someone says no, it is meant to say, or imply, for this, what you did, what asked, it was not enough. But if we are to believe the largely unconscious premise of the mind, we say no for the same reasons we say yes; for reasons that are illogical, emotional, vague, bizarre, complicated, unjust and petty.

Given this irrational force behind any ‘no’, rejection’s ultimate meaning is indeterminate, and in this indeterminacy, there is the possibility of alternative meanings.

This sounds abstract, but in a way, it is quite simple. I could read the email that tells me ‘We regret to inform you…’ blah, blah, blah, and I could think this person refused to give me a job because I made that awful typo but that would just be my attempts to control the chaos of someone else’s wanting.

The philosopher, C. Thi Nguyen, defines games as an artform in which the players participate in the “manipulation of their agency”.

Defining agency as “the ability to decide and the ability to do”, he writes that in a game, we “give ourselves over to different – and focused – ways of inhabiting our own agency.” In games, we adopt the game’s rules, adapt to its constraints, and pretend to care about its goals as a way of playing with our will.

Although I had not read Nguyen’s work in 2019, I now recognise the quest for 100 rejections as the invention of a game, of what Ngyuen calls ‘intentional gamification’ where “we design lessons from games to change our motivations in non-game activities”.

In games, we are not ourselves. In games, we get to play with our desires. I didn’t really want to apply for jobs, nor did I want to be an employee. Yet, for the sake of this arbitrary number – 100 rejections – I was willing to commit to adopting the values, constraints and rules of the desiring employee. I had to get a job, but I could choose to play a game.

The operations of the game were as follows:

I would apply for all jobs that appealed to me.

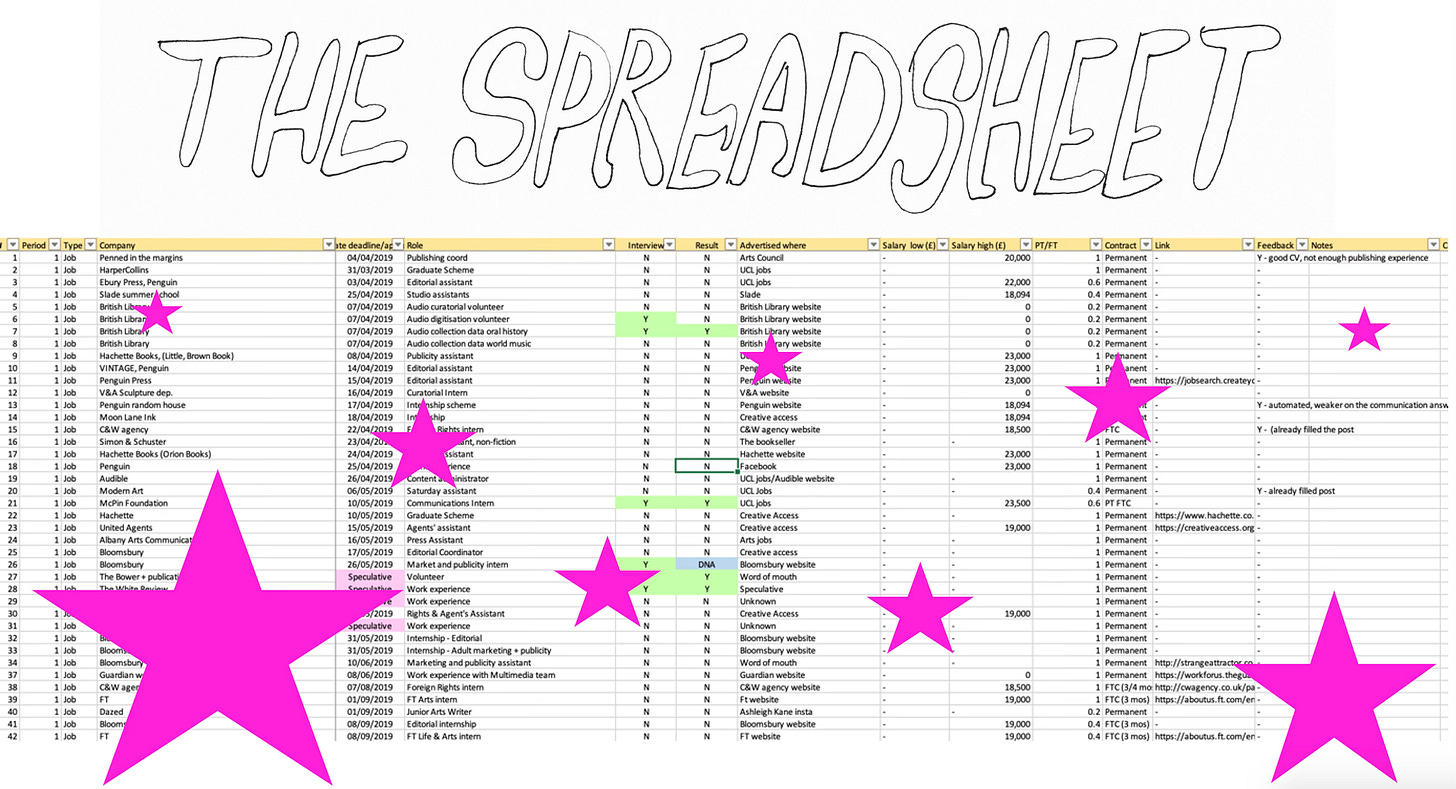

I would track all applications and all rejections using the favoured technology of the office worker, an Excel spreadsheet.

One rejection would be defined as any outright no, or any period of silent waiting that extended beyond 8 weeks.

Once I reached 100 rejections, I would get myself a prize.

Once I started to play the game of 100 rejections, the fear of the future began to change.

At night, after coming back from the studio, I would search job sites with the open aperture of the urban flaneur. I scanned listings and applied for whatever seemed curious or compelling.

I would challenge myself to do the applications quickly, not letting myself get hung up with the usual procrastination that is the outflow of fantasy. I had no visions about what any of these jobs would be like. I was focused solely on the game, and because of this focus, somehow the dullness of filling in forms became fun.

It was an exercise in chance, and best of all, I felt like I was winning because I was skewing the rules of that other game – where the employer has all the power.

In the game of 100 rejections, the no’s I received were unlike any other no I have experienced. They were meant to mean loss, humiliation, defeat, but the more I mapped my progress in the spreadsheet, the more alternative meanings emerged.

The game felt less like an appeal for work and more like a transcendent quest. On some days, a rejection represented the skewed ecstasy of courage, and on other days, a no would represent the perverse pleasure of being a little cavalier with my pride. And the more I applied, the more meanings I found.

Between April 4th and April 26th 2019, I made 19 applications. In May, I made another 17.

The plot twist came when, in the week of the degree show, after 33 rejections, I was offered a job. So, I had failed. I would not achieve my 100 no’s.

A job might seem like the end of the story, but it was not.

After I got my first job, I continued to play the game, year on year updating the sheet. It took me four years, but by 2023, I reached 100 rejections and bought myself my prize.

Nguyen explains that the agency in games is special, because in ordinary life, “struggle is usually forced on us by an indifferent and arbitrary world.” In games, it is different because our struggles are “shaped to be interesting, fun, or even beautiful for the struggler.”

I love Nguyen’s comment about how the design of games can give beauty to human struggle. But I am not sure that I agree that ordinary struggle is without shape. When I think back on my experience beginning with listening to a random podcast and then my four-year pursuit of 100 rejections, it seems to me that we constantly make real and imagined forms out of the chaos of our life’s events, forms that we use to add beauty where there might be none.

So what did I learn from this peculiar form?

For one thing, I learnt a lot of things about job applications.

Probably most importantly, I learnt that, unless you are relying on nepotism, getting a job is a matter of probabilities, markets and luck.

To want any job too greatly is to misconstrue the available information. You don’t know the history of that role, the reasons for the company hiring, their current financial position, or the wider trends and environments that affect and shape what jobs are available.

Essentially, make lots of applications and you increase the probabilities of finding a job. For me this has worked every single time I have looked for a job.

However, like Nguyen says, games are ways of shaping agency. In my case, the learning went beyond strategies and tips. Not only did the rejections re-orientate my original fear, they also reformulated my entire attitude to work.

I credit this game with an attitude that I believe is necessary for any artist who wants to have a sustainable and lasting practice.

Unless you are to be an art market darling, or you plan to receive some other combination of investment and wealth, at some point you may have to get a job. And for those artists who do have to make this choice, work need not be the dull plod of repeatable days for the sake of an income that you need but resent.

A job can be for a season, a story, an experiment. Work can be an education, a distraction, or even a way of trying on a different life. It can be a new location, a different group of people, or even a re-shaping of night and day.

To be an artist is to make art. And yet I have sat through endless meetings, sent thousands of emails, and done whatever arbitrary task was asked of me and throughout, I have known that, as Winnicott said, the meaning of this activity as it relates to my fundamental creativity was contingent. It could mean nothing, something or everything. It could mean something as slanted and skewed as those 100 no’s. It could mean I was continuing to play a game.

From all of this, you may wonder what this has to do with your next steps?

In an about turn, I am not here to advocate the game of 100 rejections. I think back on my experience of playing this game and I still don’t know what it all means, nor can I account for all of the consequences of my gameplay. And with some reflection, I can see now that the game of 100 rejections was just an elaborate method for trying to answer the question of how to continue to feel like I had creative agency when I encountered the cold indifference of an employer’s no.

As Nguyen describes in his study of games and gamification, there are risks to the “agential fluidity” of games, and the “motivational pull of clear goals and quantified scoring”, the most disturbing of these risks is the oversimplification of our values. The game sets an imperative to win and in so doing, reduces the rich and subtle complexity that drives decision-making.

Although my impulse is to suggest caution, I also want to say that what I think is relevant for others from this story of a game is that, to me, the task of life is not whether you will experience 100 rejections, or whether you will get a cool and creative job, but what you will do with the mundane forms of struggle you will encounter and how you will turn them to the task of meaning.

This is the question of general creative living, and one I hope that you will get to answer in ways that are as interesting and beautiful to you as I have come to find this imperfect and strange experiment in rejection.

💜

Thank you to Christine Kirubi who gave me the opportunity to reflect on this experience and the space to share this talk.